Vocabulary Instruction: New Words and New Meanings

The bad news: Children with limited vocabularies continue to struggle with reading and content comprehension. The good news: researchers continue to investigate the problem and frequently make new discoveries about effective methods of teaching vocabulary.

One of these exciting studies was covered in a recent edition of The Reading Teacher*. Several researchers tested two methods of vocabulary instruction recommended by some of the leading experts in literacy and vocabulary acquisition and got promising results. The methods themselves are simple, but the implications are powerful. After their teachers used specific vocabulary-building techniques, the students in the study demonstrated that they could both understand and, more importantly, accurately use a multitude of new words. The following ideas have the potential not only to impart deeper word knowledge, but also to inspire students to be word collectors and lovers of language as well. Another plus: because both methods described below can be used with any level of vocabulary, these ideas can be put to use in almost any classroom or even at home, regardless of the age or language capabilities of the student(s) in question.

Teaching New Words

Ages: All

A thoughtful parent or educator can make learning new word meanings more effective by helping children create semantically related word groupings (e.g. groups of words whose meanings are related). Begin by establishing a concept (flavor, texture, furniture, etc.) and making sure that children are familiar with the concept. This may involve asking them to reflect on their experiences with the concept or creating situations in which they can interact with and explore the idea. Next, help children to record new words that are related to this concept; older kids will probably need less support. Words can be acquired through children’s existing vocabularies, but richer responses may come through reading carefully selected texts, viewing instructional videos about the concept, or trips into the community.

Once words have been listed (a piece of paper – large for teachers of groups of students – with the concept written in the middle and semantically related words scattered around it would work nicely), guide children through a contemplation of the grouping. Words written on sticky notes, clipped to magnets on a magnet board, or typed into an interactive field on a computer can be repositioned into more specific groups. For example, when studying different kinds of furniture, students can group words according to which room the furniture should occupy, which furniture is hard versus which is soft, etc. Very young children may need an adult’s assistance to read each word. If the group is a list of synonyms for adjectives (e.g. other words for big, good, etc.), ask children to rank words from least to most extreme. Such interactions with words that fit into a pre-explored theme will make the words more meaningful for children and help them store the words correctly in the schema of their vocabularies.

Teaching New Meanings for Known Words

Ages: 3rd grade and up

This activity is best for children who are beginning to understand parts of speech.

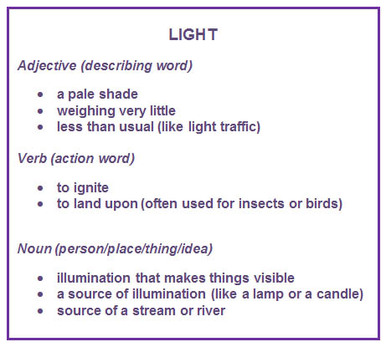

A word may be part of a child’s vocabulary, but children often have an incomplete list of known definitions from which to choose. For example, light is a word that even the youngest children know to be something that can be turned on to illuminate a dark room. But, although the word is familiar, a child may not know what to make of statements like A dragonfly might light upon a swaying reed or You should wear light clothing for hiking. A word with multiple meanings is called a polysemous word, and English is full of them. (According to the website dictionary.com, light has 42 different meanings, that’s without taking idioms into account!) To help children make sense of polysemous words, ask them to collect definitions for a given word and to list the definitions, grouped by parts of speech, on a piece of paper under the word. For example, a collection of definitions for light might look like this:

(In the case of a word with 42 different meanings and implications, it is of course not necessary to cover all of them; use your judgment to help kids create a list that is varied but not overwhelming.)

Next, explore some or all of the following possibilities:

Older children might recognize that, however it is used, light is generally associated either with luminescence or minimized mass. Ask them to explain why that might be, and guide them through the same line of thinking as they study other polysemous words. Words like head, state, land, joint, train, and plane are all excellent options. Once a word has been covered, it can be laid aside, though new definitions should be added to the paper as they are discovered through further exposure to language.

*Brabham, E., et al. (2012). “Flooding Vocabulary Gaps to Accelerate Word Learning.” The Reading Teacher, 65(8).

-Beth Guadagni, M.A.

Next, explore some or all of the following possibilities:

- Ask children to contribute drawings to illustrate each definition.

- Challenge children to add to the listed definitions and provide readings, video clips, etc. in which the word appears used in novel ways.

- Provide children with sentences using light in different ways and challenge them to determine both the part of speech and the definition.

- Ask them to make sentences using light in different ways (e.g. as a noun, as an adjective, etc.)

Older children might recognize that, however it is used, light is generally associated either with luminescence or minimized mass. Ask them to explain why that might be, and guide them through the same line of thinking as they study other polysemous words. Words like head, state, land, joint, train, and plane are all excellent options. Once a word has been covered, it can be laid aside, though new definitions should be added to the paper as they are discovered through further exposure to language.

*Brabham, E., et al. (2012). “Flooding Vocabulary Gaps to Accelerate Word Learning.” The Reading Teacher, 65(8).

-Beth Guadagni, M.A.

Photo: Erin Kohlenberg / Creative Commons